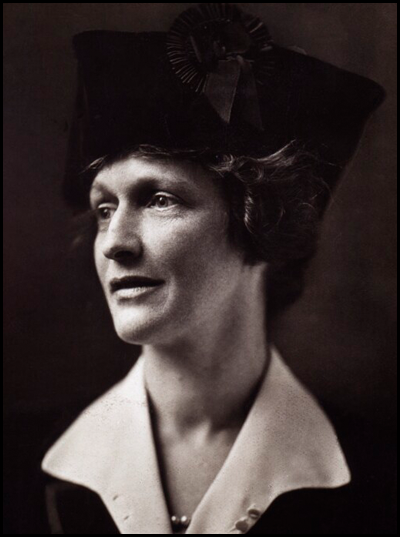

Nancy Astor, Viscountess Astor (1879-1964)

This HLF project is not one about Nancy Astor, though it was inspired by a will to find out more about the women who helped to elect her and successor women MPs. We do not include her in our resource page of biographies, and do not propose to provide a biography of her here. Instead, this page reveals why Nancy Astor is so frequently mentioned in those biographies, and why such mentions are an important part of understanding Plymouth Powerful Women, and the connections that stretch across our 100 year chronology.

When Nancy Astor first arrived in Plymouth, she was broadly interested in social activism, having had some experience of this in her early teenage years, but she had no adult experience, or understanding of the realities in the UK. Around her new married home in Berkshire, Cliveden, no opportunities had presented themselves. But with Waldorf deciding to go into politics, and to seek a seat that it would be challenging to win, the couple came to Plymouth in 1908. There she encountered a community of women who had behind them over half a century of campaigning for women’s suffrage, arguing that it was needed so that women could address the key social issues of the day. From diverse figures on the resource list, such as Mary Bayly, Clara Daymond and Louie Simpson, she learned lessons which meant that, by the time she stood for election in November 1919, she was a convinced suffragist and feminist. It is worth remembering that it was the support of Plymouth Powerful Women that convinced her to stand, finally. In both 1919 and 1922, we know that women voters were the majority of those voting in the Plymouth Sutton constituency – the figures are not available for the later elections, from 1923 on, but it seems likely that women voters were her greatest supporters throughout her parliamentary career, until she stood down in 1945.

As an MP, she continuously and persistently cited examples from Plymouth to support the points she made in support of various issues. She continued to rely on her network of Plymouth Powerful Women. The research undertaken for this project, as well as anecdotes passed on both at the Plymouth Guildhall exhibition on 28 November 2019, to launch the project initially, and from a small handful who have come forward since then to give us information, underline that local women influenced, informed and mentored Nancy in Parliament as they had done since 1908. This came from women of all kinds of backgrounds, including the March family of Stonehouse, the women of the Barbican like Bessie LeCras, and those from Plymouth’s social elite such as Agnes Buller-Kitson and Mabel Ramsay. She, in turn, mentored, influenced and informed the girls and women of a rising generation, well into the 1950s, including Laura McClure.

Alexis Bowater, the Media Adviser and Co-ordinator for this project, took up the torch of Nancy’s legacy in 2017, when she began the initiative that resulted in the raising of crowd-funding (most of it local) to enable the raising of a statue to Nancy Astor in her home city. A powerful woman herself, she was inspired by the knowledge of how much Nancy Astor had done, as a woman and for women, in being the first woman elected an MP to take her seat in the Commons, and retaining her seat for 26 years, through seven successive elections. The statue, located on Plymouth Hoe, and marking the start of our trail, was successfully unveiled by former Prime Minister Theresa May on the 100th anniversary of her election as MP being announced to the waiting crowds outside the Guildhall. As the substantial crowds and positive popular reaction from pupils and students to those events of 28 November 2019 further confirms, Nancy Astor still has the potential to influence a future, as well as the present, generation of Plymouth Powerful Women. So her place in this website is appropriate, because it frames and focuses the heritage of Plymouth Powerful Women, from those who were part of Nancy’s Network directly, to those who are now discovering her.

For further information on Nancy Astor and Plymouth, see

Rowbotham, J 2021 ‘The Returned Pilgrim’: Nancy Astor and Plymouth. Open Library of Humanities, 7(1): 6, pp. 1–21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.588.

Also see other articles in the OLH special collection, Nancy Astor, Public Women and Gendered Political Culture in Interwar Britain.

Statement about Nancy Astor

That Nancy Astor was a flawed character is unquestionable. She could be very rude to people, having a natural turn for wit this could lead her into making unfortunate statements, which did not reflect her real views or beliefs. She was undoubtedly impatient and not good at grasping abstract ideas. Plymouth is central to understanding Nancy Astor, because the city (from her arrival in 1908 in its Three Towns days on) educated Nancy Astor practically. Through her contact with Plymouth Powerful Women of all incomes, classes and experiences, she grew in character and humanity as she learned about and sought to develop strategies to help remove the challenges that Plymothians – especially women, children and young people – faced in their struggles to cope with poverty, unhealthy environments and lack of opportunities. But still she is condemned on a number of fronts.

Nancy Astor has been charged with being anti-Semitic, though she unequivocally rejected this, saying ‘I must refute your accusation that I am anti-Jewish. It is quite untrue and has caused pain not only to me but to many of my very good friends’. Her actions in Plymouth support her words, as she worked closely with the local Jewish community, and the friends she referred to included not only Lord and Lady Reading (she had been Alice Cohen, with family links to Plymouth) and Leslie Hore-Belisha, the Devonport MP, but also fellow Plymothians like Mrs Hester Robins. She is reported as saying things which offended some members of the wider Jewish community, but recent research underlines that she was often deliberately or accidentally misquoted by those who disliked her, both personally and politically, and who wanted to undermine and damage her reputation. We will never know for certain whether she actually said some of these things, but if she did, the evidence from Plymouth in particular suggests that they will have been due to a lack of knowledge or understanding of the wider global Jewish community.

She has also been accused of being anti-Roman Catholic. There is some evidence to suggest that she distrusted the Vatican, and its policies, seeing these as divisive in a number of areas including homosexuality and potentially undermining of projects to promote world peace. However, in Plymouth, two of her closest friends and co-workers in projects relating to nursery and day care provision, maternity welfare, the need for opportunities for young people, safe sport and leisure provision were two successive Roman Catholic Bishops of Plymouth, Bishop John Joseph Kiely (1911-1928) and Bishop John Barrett (1928-1946). She regularly attended prize-giving ceremonies at Notre Dame School for Girls, as well as helping to organise and opening fund-raising bazaars for Roman Catholic charitable initiatives locally.

It has been suggested she was pro-Nazi, but she was instead amongst the first women in the UK to condemn the Nazi Party, especially for its policies towards women. On 31 May 1933, she was one of the organisers (with Viscountess Rhondda and Eleanor Rathbone MP) of a meeting of women’s organisations to discuss and condemn Nazi Party policies towards women. The meeting at the Commons was hosted by Eleanor Rathbone, and Nancy proposed the unanimously adopted resolution roundly condemning those policies – the motion was then sent to the British Ambassador. Nor was she pro-fascist. She knew Sir Oswald Mosley, and he campaigned for her re-election in 1922, but it was his first wife, Cynthia, who was Lady Astor’s friend. She broke with Mosley after Cynthia’s death and never forgave him (or Diana Mitford) because she believed they were responsible for Cynthia’s untimely demise. She was hostile to both Communism and Facism as belief systems because they contradicted her liberal values, but her understanding of the abstractions involved was frankly limited – a consequence of her intellectual inability to grasp abstract consequences, and to prefer practical demonstrations made before her eyes.

She was certainly, like most women politicians and activists in the interwar era, a believer in the importance of global peace, becoming involved with a range of international women’s organisations concerned with that goal from the 1918 Armistice on. But while that certainly led her to support the League of Nations, and its attempts to control Hitler and Mussolini’s ambitions, she had largely lost faith in the League by 1936. She continued to hope for the maintenance of peace, but from 1936 on, she and Eleanor Rathbone were the most vocal women MPs in favour or rearmament – hardly surprising given that she was an MP for Plymouth, and defence and defence spending were vital to her constituents. Her position was that, for the sake of women and children in particular – the greatest sufferers in any conflict, war should be avoided but not at all costs. The nation had to be both prepared and willing to fight should maintenance of peace become IMpossible, something she recognised as likely from 1938 on.

While she was often unwise and impulsive, as the comments above underline, there is one absolute certainty about Lady Astor. It is that at the time and even now, the most controversial thing about Nancy Astor was that she was a woman who chose to challenge the conventions of the day by engaging with politics and seeking to do so on equal terms with her male peers.